Looking Back 100 Years--And Finding Ourselves

In my home state of Colorado, the past is not as much studied as it is mythologized. When people try to imagine what it must have been like in the days of “the Old West” – say, around 1864 or so -- they are more likely to be thinking of gunslingers and cavalry troops as portrayed in John Ford or Clint Eastwood movies, rather than the real-life tragedy of the Sand Creek Massacre, an atrocity many of my neighbors have never heard of.

The same could be said about the 1920s. For most of us, the frame of reference is a montage of Hollywood imagery. Flappers and speakeasies. Fitzgerald and Hemingway. Al Capone and Lucky Lindy. Model Ts and hot jazz, roaring good times and a crash looming around the corner. These standard reference points help to keep the past at some distance from us, like it’s an episode of "The Untouchables" or some other chestnut, a melodrama we’ve already seen and have no need to revisit. But once you get beyond the usual cliches, you start realizing that the past is a lot closer than you thought.

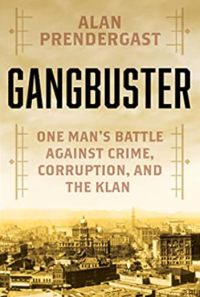

In fact, what set me on the path to GANGBUSTER, my book about a 1920s district attorney who tries to prevent the Ku Klux Klan from taking over his town and his state, was the discovery of how familiar the whole story is — not in the sense of a show already seen, but in the many ways life in Denver a century ago resembles what America is going through now.

Consider a few of the more obvious similarities. At the start of the decade, the country was emerging from the dual traumas of war and a pandemic that killed millions. Rising crime was a major concern, along with steeply rising prices. Rapid technological innovation was disrupting traditional ways of living and doing business. Fear of not keeping up with more prosperous neighbors mingled with fears about the increasing presence of immigrants who spoke in languages other than English and belonged to faiths other than Protestantism. The electorate was polarized over many issues with profound social and cultural implications, from the labor movement to teaching evolution in schools to women’s rights.

These are, admittedly, superficial comparisons. I’m not trying to make the case that the two eras share the exact same problems, that we’ve learned nothing in a hundred years. But I would suggest that there’s a great deal we can learn from what happened a century ago, as long as we ask the right questions. For example: how did the resentment of immigrants help to fuel reactionary movements like the Ku Klux Klan, which called on America’s white, native-born Protestants to defend “100% American” values? How did such a brazenly racist organization, birthed in the Deep South, attract millions of followers and become a mainstream political force in places like Colorado? And how do you expose the crimes of such a group when local police, the courts, and the press are complicit in its rise to power?

It was with the aim of tackling questions like these that I got involved in the deep dive into the 1920s that would become GANGBUSTER. I can’t claim to have found all the answers, but I have found aspects of the story that resonate strongly with the culture wars and implacable political divide we’re facing today.

At times the past is a mirror—and we can see ourselves in it and learn from it.